An Investigation Into How Compute Shaders Can Be Used to Model Hydraulic Erosion in Games

Computer Games Programming Bachelor Thesis by Lily Raeburn

Introduction

Literature Review

Overview

The Purpose of Hydraulic Erosion

Hydraulic Erosion Currently

Techniques of Hydraulic Erosion

Simulating Hydraulic Erosion Using Shaders

Summary

Output Design

Bibliography

Glossary of Terms

Introduction

Context

This research project will investigate shader programs (commonly referred to as shaders) which are files containing code designed to run on a Graphical Processing Unit (GPU). Shaders are a type of computer program that is specifically designed for shading and special effects in games but can be extended to have alternate functionality. Although shaders are usually written and optimised to run on GPUs this is not a requirement and they can be run on Central Processing Units (CPUs). Bergstrom (2014) explains shaders are usually used to draw geometry to the screen, this is most often associated with image effects in games although they can also be found in other mediums that contain a rendered image. Doppioslash (2018) elaborates on this definition by talking about the different types of shaders such as vertex shaders that calculate the position of vertices and fragment shaders that calculate the colour of a pixel. Since vertex and fragment shaders are now considered old tech, newer shaders, namely geometry and compute, have been introduced that are optional but offer different functionality. The geometry shader is used in conjunction with vertex shaders in order to add extra geometry to a vertex stream. A compute shader can be used for any calculations although typically they are not part of a rendering pipeline and have to be dispatched by the CPU.

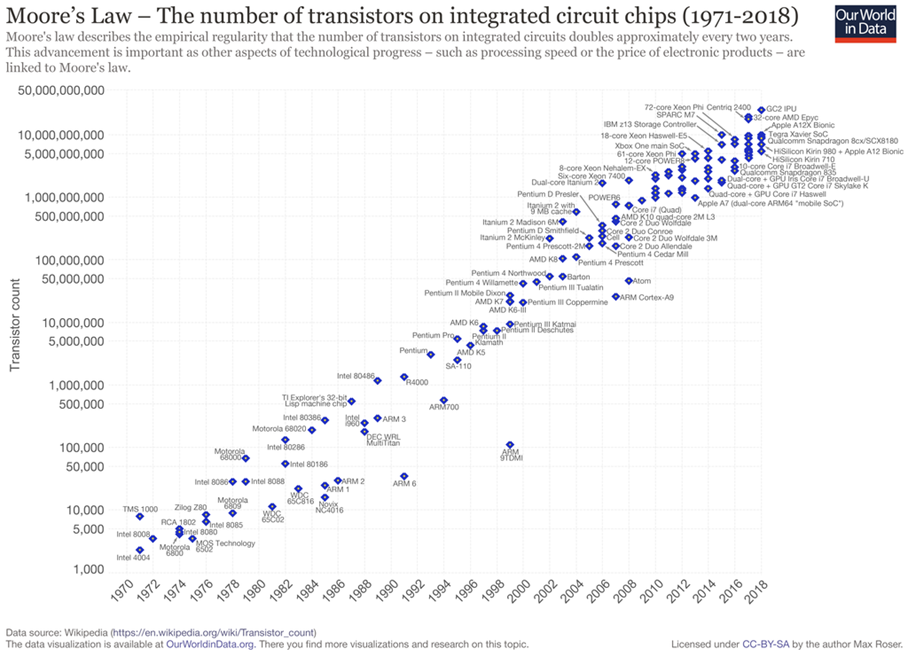

Hydraulic erosion is the process of flowing liquid wearing down and aging surfaces by dislodging and moving sediment from one location to another. Beneš (2006, p17) observed why this is important for games when they said, “Of all the weathering phenomena that can be observed in Nature, hydraulic erosion has the most visual importance.”. It has also been discussed that as computer graphics have evolved in the last twenty years natural phenomena such as weathering, erosion, and morphology have been in the spotlight and have undergone massive developments. Even though these phenomena are important in games they can be challenging to simulate effectively. For static pre-made game worlds this is not a problem as the simulations can be run outside of the game and then saved and imported. However, for real time simulations to be possible the efficacy of the simulation must be refined. Beneš (2006, p20) describes how this could be achieved with the GPU: “One of the problems is the speed of the simulation. The actual calculation of three minutes of a voxel space in resolution 3003 takes several hours on a computer with a 3GHz CPU. One of the possible methods of increasing the speed could be using GPU.”. However, this source is from 2006 and there have been considerable improvements in hardware. It is shown in figure 1 that the tech industry has evolved since, with new products and software iterations launching on the consumer market all the time. A source that at the current date is thirteen years old, might not completely reflect the current realities.

Figure 1: A graph showing the effect of Moore’s Law over time from OurWorldInData (2019).

Objectives

Research existing solutions for hydraulic erosion simulations using compute shaders.

Determine the techniques of existing hydraulic erosion simulations.

Review the effectiveness of existing hydraulic erosion simulations.

Create a terrain erosion solution using the appropriate techniques and the Unity (Unity Technologies, 2019) game engine.

Literature Review

Overview

This literature review will discuss the current techniques of hydraulic erosion simulations, the purpose of simulating this phenomenon, the benefits and drawbacks. The opinions of authors will be contrasted and compared to give an all rounded view of the issues with simulating hydraulic erosion. The issues will be followed by a summary of the findings of this research. Although it is possible to both model and render hydraulic erosion, this review will only discuss modelling and the manipulation of terrain.

The Purpose of Hydraulic Erosion

Since the inception of video games, a percentage have continually pushed for more visual realism. Examples of technological advancement can clearly be seen through games such as Pac-Man (1980), The Elder Scrolls: Arena (1994), King’s Field IV (2001), Mass Effect (2007), and GTA V (2013). However, most game graphics have been limited by the consumer level hardware of their time, as shown in Figure 2. Also shown in Figure 2 is another example of graphical improvements over time, where two entries in the same franchise have significantly improved visual realism between releases. A realistic environment is often the backbone for games that offer outdoor scenery. Deussen, Neidhold, Wacker (2005) back this up by discussing how important realistically eroded terrain is to a visual representation. This notion could indicate that as game visuals become more important, more detail is needed to create a visually complex, and therefore realistic, scene.

Figure 2: A small mountain in GTA:SA (2004) versus a mountain in a later instalment of the same franchise, GTA V (2013).

Since a significant portion of games are consistently pushing for more detail across larger areas/assets, a strain is put on designers and games companies alike to always improve and adapt to new graphical requirements. It further leads to programming AI to build terrain instead of modelling it by hand due to time constraints. A simple solution for this problem would be to implement automatic content creation such as procedural generation (PG), which transfers the workload onto computers; allowing for virtually limitless asset creation with no strain upon deadlines. An example of procedurally generated content with almost no limitations can be seen in Figure 3. Another effective implementation can be seen in figure 4 in which a world sized at 32 million by 32 million blocks is achievable through an input of a few hundred hand crafted assets.

Figure 3: An in-game screenshot of No Man’s Sky (2016).

This would come at the cost of control over assets and cannot guarantee that an asset will look good or even be usable without huge amounts of fine tuning, which is the problem designers are trying to avoid in the first place. It could be suggested that PG tools are much more beneficial to smaller games companies who do not have the time, resources, or skills necessary to create realistic looking terrain and rely wholly upon PG tools.

Figure 4: An in-game screenshot of Minecraft (2011).

Tools have been designed that allow designers to combine the speed and convenience of PG techniques with the precision of manual design. A good example of such tools would be Houdini (1996) which includes key features promoting the use of built-in and custom programmable PG. Although PG tools can speed up development, more complex cases can require advanced hardware and generous compute times. Other simpler PG tools include SpeedTree from BiteTheBytes (2014) and World Creator from Interactive Data Visualisation, Inc. (2017).

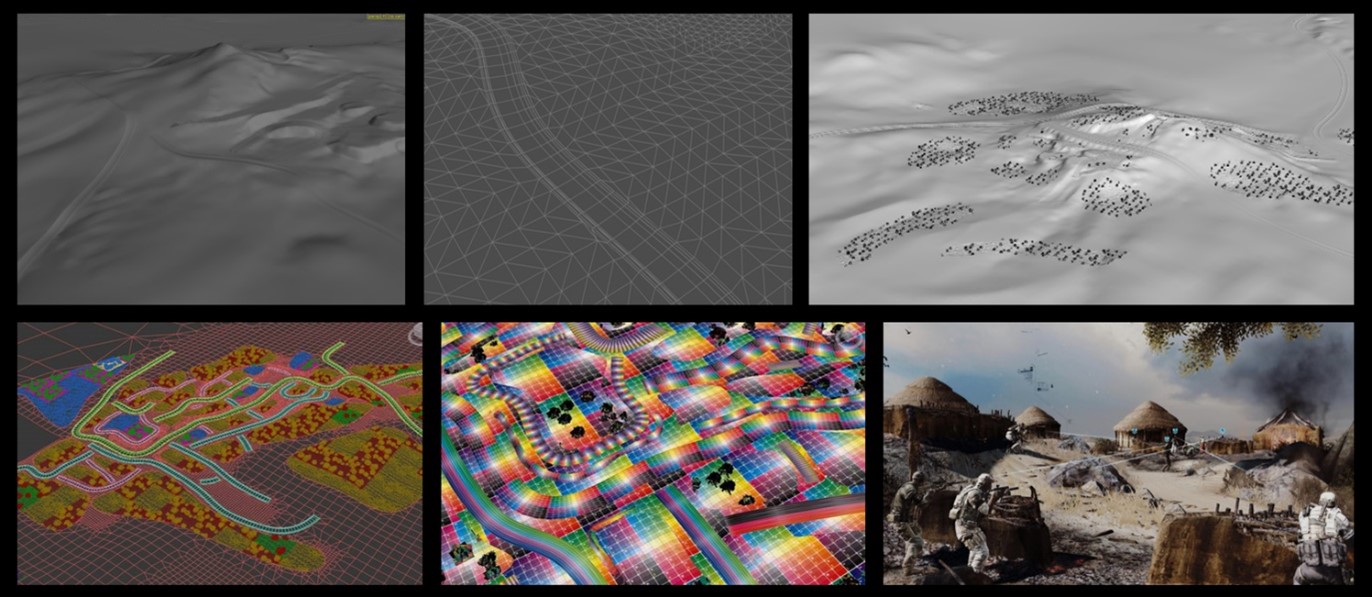

Kenwood, Gain, and Marais (2014) describe how creating a forest using PG tools can use up to 10MB per tree and compute times can last for hours. Since the advent of such tools it has been possible to create detailed worlds on a scale not seen before. Werle (2017) expands on this by detailing how they used procedural tools, specifically hydraulic erosion, to create the world map for Wildlands (2017) which has been estimated at roughly 400km2. By using tools such as ‘brushes’ on terrain designers can add and remove features on a large scale on a whim. These features can be mixed, rotated, and overlaid with ease allowing for a very efficient way to create great looking game worlds. The alternative to these techniques would be designers modelling terrain by hand, from scratch, which would be far more difficult and time consuming. An example of PG terrain tools can be seen in figure 5, where systems such as brushes, roads, erosion, and more are used.

Figure 5: Images of Houdini Terrain Tools (2017) used in creating Wildlands (2017).

Hydraulic Erosion Currently

The topic of simulating hydraulic erosion started around 60 years ago. Although there is some prior research, a paper by Schenck (1963) stands out as the first major look into simulating hydraulic erosion. Schenck’s paper has been referenced 66 times in material concerning hydraulic erosion according to Google Scholar (Google, 2004) which makes it one of the most cited papers on this topic. Schenck specifies a technique to simulate drainage networks through a random-walk algorithm. The random-walk algorithm is not dissimilar to a basic maze generator and was designed to be simple so it could run on the confined technology of the time. Although outdated, the information provided by Schenck later formed the basis of algorithms used today for hydraulic erosion.

When generating hydraulically eroded terrain it is assumed that there will be an input for the algorithm to work from. Since there are currently two distinct and widely adopted techniques for hydraulically eroding terrain, as stated by Beyer (2015), the input will need to be in one of two formats. The first is a heightmap that describes the terrain height at each vertex from a bird’s eye perspective. The second is a voxel grid structure that can map hydraulic erosion in all 3 dimensions.

The effect of hydraulic erosion can be viewed on either a large or small scale. Nguyen, Benahmed, Philippe, and Diaz Gonzalez (2017) refer to these effects as micro and macro erosion. Macro erosion is caused by large bodies of liquid such as a river, stream, or lake and would cause erosion on a large scale. Micro erosion is caused by smaller amounts of liquid such as rain drops and is much subtler in appearance. Macro erosion is essentially the result of lots of Micro erosion in one area.

Techniques of Hydraulic Erosion

Papers by Beyer (2015), Beneš (2006), and Neidhold (2005) have shown there are two distinct methods to simulate hydraulic erosion. The first is commonly referred to as the Eulerian (grid) method and is implemented using a grid/heightmap which stores terrain height at each point. Heightmaps are already commonly used to efficiently store terrain data, this makes it relatively straightforward to couple with the Eulerian method which is also represented with heightmaps. Overall cells with four layers are used to store terrain height, amount of liquid in a cell, amount of sediment in a cell, and current liquid velocity. These cells can be extended to store 3D terrain data which is known as a voxel grid. Since heightmaps are a 2D representation of 3D terrain it impossible to store concave geometry, voxel grids solve this problem and allow for caves and overhangs. Dorsey (2005) suggests implementing methods of compression such as octrees and run length encoding (RLE) in order to more efficiently store voxel data. A more up to date source from Beneš (2019) also suggests using RLE as it allows for lossless encoding of data as well as scrolling through a hydraulic erosion animation if one is required. This would reduce memory usage and potentially increase the speed and accuracy of the simulation as more simulation time would be spent on perimeter voxels and therefore areas which are more likely to be eroded.

The Langrangian (particle) method simulates erosion by treating each unit of liquid, typically a raindrop, as a particle on the terrain it is eroding. This method would store how much liquid it contains, its position, velocity, and sometimes mass depending on implementation. Due to this a particle cannot distribute liquid in more than 1 direction, which leads to lesser accuracy with this method whereas on a grid, liquid can be distributed in multiple directions to other cells. In each step of a simulation a particle will move in a direction based on the height of its grid neighbours. Before the particle is moved the amount of sediment to absorb will be calculated. After the particle has moved the amount of sediment to deposit and how much liquid will evaporate will be calculated. All these variables are dependent on the calculations from the previous step. Beyer (2015) has discussed how the Eulerian method is more accurate than the Langrangian method at the cost of computation time. The Eulerian method stores cells in an array that is the same size as the input heightmap. A cell would store how much liquid it contains, how much liquid is distributed to neighbouring cells, and how much liquid is received from neighbouring cells.

Although the main ways to simulate hydraulic erosion have now been covered, there are still some legacy and non-simulated methods to generating eroded terrain. The oldest terrain generation method uses fractals and was pioneered by Perlin (1985) and had some continuation by Musgrave (1989). Terrain is generated by an algorithm that takes a seed and outputs in two dimensions; the output can then be stored in a heightmap. This method is fast and requires little storage however cannot produce accurate, natural looking, or mathematically correct terrain as stated by Musgrave (1989). Kelley (1988) introduced river-based generation that extended fractal generation. River-based algorithms are limited to small terrains and have no user input. Fractal generation can again be extended by sketch-based generation, where a sketch of a heightmap and a fractal heightmap are combined. Both Zhou et al (2007) and Hnaidi et al (2010) discuss this method of generation and how it gives the designer some control over the output with the caveat of the output not having erosion simulated on it, so it still won’t be geologically accurate. Sketches must also exactly match the size of the original heightmap which slightly limits scaling.

Each cell in a grid-based setup would need to be updated individually each step which makes this approach very expensive and only suitable on simulations that contain a large Liquid to Terrain Ratio (LTR). The particle approach can be used instead for a cheaper, more scalable solution and can be combined with heightmaps to store the erosion. This method does not require all the cells to be updated every step, only the current active particles and the neighbouring cells. Eroding terrain using rainfall would give a small LTR making particle erosion the best choice. If there is a river or a lake in the terrain this would significantly boost the LTR and therefore the Eulerian method might be the better choice. The maths for these methods is the same, only the implementation differs. There are five main operations involved in simulating hydraulic erosion: liquid distribution, terrain erosion/dissolving of sediment, liquid relocation, sediment deposition, and water evaporation.

Liquid distribution can be as large as the mouth of a river or could be as small as a raindrop. Since liquid erosion is typically a slow process and a simulation of this process is attempting to be efficient there is some deliberation to be made about whether liquid should be added all at once or continuously for the duration of the simulation. For example, an implementation by Beyer (2015) allowed for continuous rainfall over terrain whereas Beneš (2019) chose to add all the liquid at the beginning and the simulation ends when no liquid remains. This trend can be seen in more papers and no standard has yet been reached.

The Navier-Stokes equations are often used in liquid simulations to provide a mathematically accurate method of calculating liquid velocity and pressure. These equations often form the foundation for simulations and allow transporting of sediment and water evaporation. Since speed is a priority and accuracy is secondary, these equations are usually simplified and optimised so that they can be calculated faster even though the result might be slightly worse. Since these calculations are performed many times on different areas of a terrain the difference in quality is usually not noticeable or consequential. Authors such as Beneš (2006), Selle (2007), and Neidhold (2005) demonstrate modified fluid dynamic equations based off the Navier-Stokes equations in order to optimise without much loss to accuracy. There are some implementations that use the full Navier-Stokes equations however for games this is not a necessity.

For the simulation to know which way liquid should move, a path of least resistance must be found. A simple way to find this would be to compare the heights of the current grid cell and its neighbours and choosing the direction of the cell with the lowest height. More complex methods have been discussed by Beyer (2015) where a gradient map was created using bilinear interpolation of the surrounding cell heights. The gradient map can then be used to more accurately calculate the new velocity for liquid. Mei (2007) takes this a step further by discussing how inflow and outflow of neighbouring cells can affect the velocity of the liquid in the current cell. For simulating rainfall, more primitive methods can be employed as it will not make a difference in the output. However, when simulating large bodies of liquid that can flow, or when visualising a simulation, the latter method should be used for higher accuracy.

The erosion of terrain and transferal of sediment into liquid comes after liquid distribution and is calculated every step alongside liquid movement. One unit of liquid is only capable of carrying an amount of sediment which can be defined through a capacity constant. The rate of deposition and dissolution can also be described through constants. Through these constants it is possible to describe and simulate a range of liquids which can then result in differing outputs. The amount of sediment to deposit and dissolve on each simulation step can be determined by the amount of sediment already being carried by a unit of liquid.

The evaporation of liquid must also be considered as the amount of water in any cell or particle defines how much sediment it can carry, if any.

Hydraulic erosion only counts for one part of all weathering and eroding systems that sculpt the way landscapes look. Although it is not necessary, combining hydraulic erosions with other erosion and weathering systems such as thermal weathering, which describes the slippage of large pieces of sediment that are often deposited at the base of a mountain causing a talus slope effect. An example of a Talus slope can be view in figure 6.

Figure 6: An example of a Talus slope at the base of a mountain by Hendrix and Hendrix (n.d.).

Simulating Hydraulic Erosion Using Shaders

Whatever engine and programming language are chosen to setup the project, it is guaranteed that a shading language such as High-Level Shading Language (HLSL) or OpenGL Shading Language (GLSL) will be used to develop shaders. When developing a hydraulic erosion simulation, the simplest way is to have a program that takes an input terrain, runs, and outputs a terrain. This approach might be initially hard to setup and debug but since nothing is rendered it makes for a more lightweight and streamlined program. Simulations can be mixed with visualisations which is a much more heavy-duty approach with the added benefit of seeing the output making debugging easier. Since visualisations have to be run almost in parallel with the erosion simulation it is better in this approach to run small sections of the simulation at a time and let the user decide when to stop. A game engine can be used in order to simplify a visualisation. Beyer (2015) uses the Unity (Unity Technologies, 2005) engine for rendering and visualisation whilst utilising the ShaderLab shading language for the simulation. Other software such as Houdini (1996) are specifically built for functions like this and can provide a much quicker way of developing a visualisation for the simulation.

Summary

In summary simulating hydraulic erosion allows for a fast and precise method of producing realistic looking terrain however can only be used on open terrain. Although games companies are pushing for innovative games all the time, not all of them can be open world and so hydraulic erosion is not appropriate everywhere. Procedural Worlds (2018) states that the best use for hydraulic erosion would be to use in very early or late stages of terrain development, either as a starting point or to add realism at the end to give designers more control over environment creation.

To summarise simulation techniques:

Fractals are fast however offer little to no realism or user control.

Heightmap, voxel grid, and particle-based erosion gives the best results but still offers little user control.

Sketch-based simulations offer more control for designers however still offer little to no realism and are limited by the size of the original heightmap.

River-based simulations offer almost no control and cannot produce large detailed terrain.

Output Design

Introduction

The output product will be a system built within the Unity (Unity Technologies, 2005) game engine, version 2019.1.9f1, that can hydraulically erode terrain by using shaders. Alongside the simulation will be a visualisation so that the user may review the simulation and stop at any time, alternatively an option to ‘render’ the simulation in batches could be added without visualisation in order to use more processing power on the simulation making it quicker. Either the heightmap or the particle method will be used as they are both well documented and can be achieved in the current time step. The system should be able to take a single heightmap representing terrain as an input, modify the input, and when the simulation is complete save the output back to the original file. Since simulation and visualisation can run directly off the GPU, simulation data will only be sent to the GPU at the start and collected at the end.

The simulation will focus on the idea of rainfall and not include large bodies of water such as rivers or lakes. The system will take inputs such as the length of virtual time to run the simulation or alternatively how many raindrops to simulate. The system should be scalable in what sizes of terrain it can run on in order to maximise efficiency for the user.

An effort will be made to include more user control into the output since that is currently the main issue surrounding the use of this method. This would most likely take the form of a ‘brush’ style tool that allows a user to erode patches of a terrain instead of the whole terrain at once. Another method to add more user control would be to combine the sketch method and allow for heightmap sketches to be added into terrain. The output will be designed for use in Unitys editor mode so that users can effectively and easily created eroded terrain. A balance between realism and performance is necessary as the tool should be quick to use, some features such as a preview could be added in order to save time on a final ‘render’; this could improve the ergonomics of the system greatly.

The system will exist as either a tool window within Unity, or as a script that can be attached to a terrain object. The former is more desirable as it would allow more flexibility when working on multiple terrains and the code should not be present at runtime unless a games central themes rely on it.

Bibliography

References

Beneš, B. (2019). Physically-Based Hydraulic Erosion. In: Spring Conference on Computer Graphics. [online] New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, Inc, pp.17-22. Available at: https://dlnext.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/2602161.2602163?download=true [Accessed 20 Oct. 2019].

i>Beneš, B., Těšínský, V., Hornyš, J., and Bhatia, S.K., (2006). Hydraulic erosion. Computer Animation and Virtual Worlds, 17(2), pp.99-108.

Bergstrom, S. (2014). Shaders: A primer. [Blog] Gamasutra. Available at: https://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/SvenBergstrom/20140407/214788/Shaders__A_primer.php [Accessed 2 Oct. 2019].

Bethesda Softworks, (1994). The Elder Scrolls Arena. Video game, MS-DOS, Maryland, U.S.: Bethesda Softworks.

Beyer, H.T., (2015). Implementation of a method for hydraulic erosion. Bachelor’s Thesis in Informatics: Games Engineering, [online] Available at: https://www.firespark.de/resources/downloads/implementation%20of%20a%20methode%20for%20hydraulic%20erosion.pdf [Accessed 26 Oct. 2019].

BioWare, (2007). Mass Effect. Video game, Xbox 360, Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, Xbox 360, Xbox One, Wii U, Washington, U.S.: Microsoft Game Studios.

BiteTheBytes, (2014). World Creator. Fulda, Germany.

Doppioslash, C. (2018). Physically based shader development for Unity 2017. Liverpool, UK: Apress.

Dorsey, J., Edelman, A., Jensen, H.W., Legakis, J., and Pedersen, H.K. (2005). Modelling and rendering of weathered stone. ACM SIGGRAPH 2005 Courses (p.225–234). ACM.

Engel, W. (2016). GPU Pro 7. Natick: CRC Press.

FromSoftware, (2001). King’s Field IV. Video game, PlayStation 2, Tokyo, Japan: FromSoftware.

Google Inc. (2004). Google Scholar.

Hello Games, (2016). No Man’s Sky. Video game, Microsoft Windows, Playstation 4, Xbox One, Guildford, England: Hello Games.

Hendrix, M., and Hendrix, J. (n.d.). Talus Slope. [image] Available at: http://travellogs.us/Miscellaneous/Geology/Talus/Talus.htm [Accessed 11 Nov. 2019].

Hnaidi, H., Guérin, E., Akkouche, S., Peytavie, A., and Galin, E. (2010). Feature based terrain generation using diffusion equation. Computer Graphics Forum, 29(7), pp.2179-2186.

Interactive Data Visualisation, Inc., (2017). SpeedTree. Lexington, South Carolina.

Kelley, A., Malin, M., and Nielson, G. (1988). Terrain simulation using a model of stream erosion. Proceedings of the 15th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques - SIGGRAPH '88.

Kenwood, J., Gain, J., and Marais, P., (2014). Efficient Procedural Generation of Forests. Available at: http://wscg.zcu.cz/wscg2014/Journal/I59-full.pdf [Accessed 29 November. 2019]

Mei, X., Decaudin, P., and Hu, B.G., (2007). Fast hydraulic erosion simulation and visualization on GPU. In 15th Pacific Conference on Computer Graphics and Applications (PG'07) (pp. 47-56). IEEE. [online] Available at: http://nlpr-web.ia.ac.cn/2007papers/gjhy/116.pdf [Accessed 07 Nov. 2019]

Mojang, (2011). Minecraft. Video Game, Microsoft Windows, MacOS, Linux, Stockholm, Sweden: Mojang.

Musgrave, F.K., Craig, E.K., and Robert, S.M. (1989). The Synthesis and Rendering of Eroded Fractal Terrains. Proceedings of the 16th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques - SIGGRAPH '89, [online] pp.41-50. Available at: https://dlnext.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/74333.74337?download=true [Accessed 22 Oct. 2019].

Namco, (1980). Pac-Man. Video game, arcade, Tokyo, Japan: Namco.

Neidhold, B., Wacker, M., and Deussen, O. (2005). Interactive physically based fluid and erosion simulation. Goslar, Germany: Eurographics Association.

Neidhold, B., Wacker, M., and Deussen, O., (2005). Interactive physically based Fluid and Erosion Simulation. Eurographics Workshop on Natural Phenomena. [online] Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f5e8/a436fb57e890b458f88d85588f53e0712fbb.pdf [Accessed 07 Nov. 2019]

Nguyen, C., Benahmed, N., Philippe, P., and Diaz Gonzalez, E. (2017). Experimental study of erosion by suffusion at the micro-macro scale. EPJ Web of Conferences, [online] 140, p.09024. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318067996_Experimental_study_of_erosion_by_suffusion_at_the_micro-macro_scale [Accessed 29 Nov. 2019].

OurWorldInData, (2019). A plot (logarithmic scale) of MOSFET transistor counts for microprocessors against dates of introduction, nearly doubling every two years. [online]. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/uploads/2019/05/Transistor-Count-over-time-to-2018.png [Accessed 28 November 2019].

Perlin, K. (1985). SIGGRAPH '85 conference proceedings, July 22-26, 1985, San Francisco, California. New York, N.Y.: Association for Computing Machinery, pp.287-296.

Procedural Worlds. (2018). Unite Berlin 2018 - Worldbuilding in Minutes Rapid Procedural Terrain & Scene Creation. [video] Available at: https://youtu.be/YPCghfsHdSg [Accessed 11 Nov. 2019].

Rockstar North, (2004). Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas. Video game, Microsoft Windows, Playstation 2, Xbox, New York City, U.S.: Rockstar Games, Inc.

Rockstar North, (2013). Grand Theft Auto V. Video Game, Microsoft Windows, Playstation 4, Xbox One, New York City, U.S.: Rockstar Games, Inc.

Schenck, H. (1963). Simulation of the evolution of drainage-basin networks with a digital computer. Journal of Geophysical Research, [online] 68(20), pp.5739-5745. Available at: http://www.uvm.edu/pdodds/files/papers/others/1963/schenck1963a.pdf [Accessed 21 Oct. 2019].

Selle, A., Fedkiw, R., Kim, B., Liu, Y., and Rossignac, J., 2007. An Unconditionally Stable MacCormack Method. [online] Available at: http://physbam.stanford.edu/~fedkiw/papers/stanford2006-09.pdf [Accesed 07 Nov. 2019]

Side Effects Software Inc., (1996). Houdini. Toronto, Canada: Side Effects Software Inc.

Št'ava, O., Beneš, B., Brisbin, M., and Křivánek, J. (2008). Interactive Terrain Modeling Using Hydraulic Erosion. Eurographics/ ACM SIGGRAPH. Available at: http://hpcg.purdue.edu/bbenes/papers/Stava08SCA.pdf [Accessed 13th October 2019]

Ubisoft (2017). Ghost Recon: Future Soldier – Houdini Terrain tools. [image] Available at: https://80.lv/articles/procedural-technology-in-ghost-recon-wildlands/ [Accessed 29 Nov. 2019].

Ubisoft Paris, (2017). Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon Wildlands. Video game, Microsoft Windows, Xbox One, Playstation 4, Montreuil, France: Ubisoft.

Unity Technologies. (2005, June). Unity.

Werle, G., and Martinez, B. (2017). 'Ghost Recon Wildlands': Terrain Tools and Technology. Game Developers Conference, 27 February, San Francisco. Available at: https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1024029/-Ghost-Recon-Wildlands-Terrain [Accessed 24 October. 2019].

Zhou, H., Sun, J., Turk, G., and Rehg, J. (2007). Terrain Synthesis from Digital Elevation Models. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 13(4), pp.834-848.

Glossary of Terms

Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas – GTA:SA

Grand Theft Auto V – GTA V

Rockstar Games, Inc. – Rockstar

Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon Wildlands – Wildlands

Step – One cycle of a simulation